My sons piano lessons sire me an opportunity to squint at piano sheet music up close.�Piano scores seem to have a unique visual eyeful that music written for other instruments doesnt quite match.�Im writing this without taking a squint at Childrens Corner (L.113), a six-movement suite for solo piano by French composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918).

The very first movement is titled Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum, a satirical dig at piano exercises (some say specifically those of Carl Czerny), often tabbed Gardus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus). Parnassus is the loftiest part of the mountain range in inside Greece, the name itself literally meaning mountain of the house of God and occupies an important place in Greek mythology.

As you can imagine, both the visual and within contours of the score are craggy, sometimes perfect symmetrical peaks in a measure, sometimes jagged and serrated.

Not all scores are eye-catching, of course. But the score of the fourth movement of Childrens Corner, The Snow is Dancing does have an ordered jollity well-nigh it, just visually speaking. Maybe Im unjust from prior knowledge of the music and the title. But if you considered the score as some sort of Rorschach test, I think youd stipulate with me. The notes in the upper and lower staves are joined in the middle, so that the horizontal double lines joining them from the waist, the upper notes the heads and the lower notes the legs of dancing couples. In some measures, the slurs plane make them seem as if they are using a jumping-rope to skip in playful abandon! You can trammels these out for yourself by seeking out the sound-tracks on YouTube that have the twin music score.

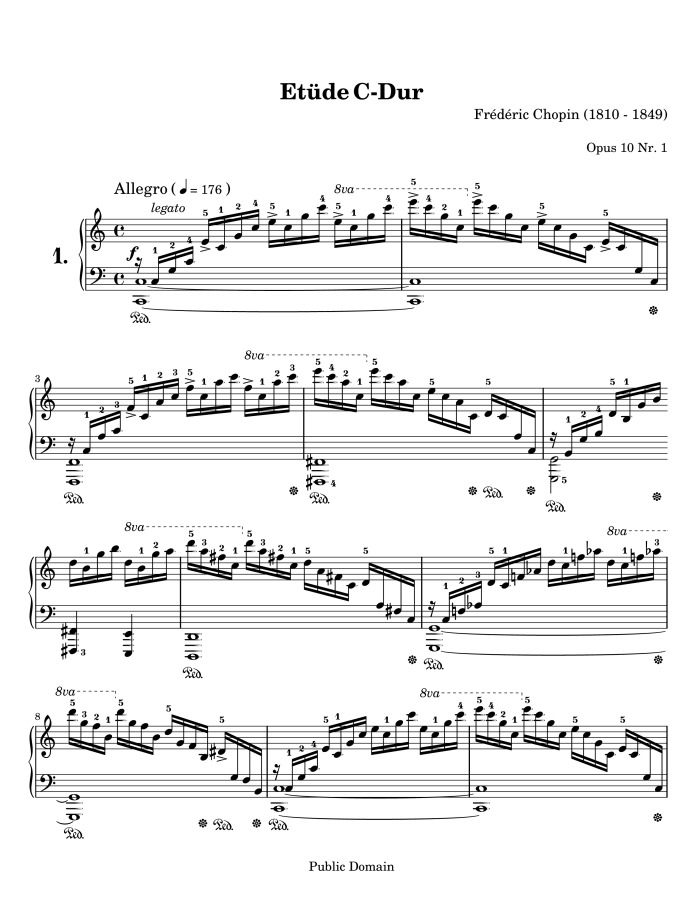

Im obviously not the first to be struck by the physical eyeful of the music score. The American music critic James Huneker (18571921) wrote of the hypnotic charm for eye as well as ear of Fr�d�ric Chopins �tude Op. 10, No. 1 (the Waterfall, a visual image right there in the title) in the installment “The StudiesTitanic Experiments” from his typesetting Chopin: The Man and His Music (1900).

But let me tell you here of my own visual connection with this Chopin �tude. Around the 1980s in the pre-internet era, the first ten measures or so of this work were the soundtrack to some Indian television advertisement. The purpose of any telecast is that the consumer should remember the product. But this ad was so seductive that I remember the pretty woman secretive, in some sort of pall with a cape, and this music that trailed off without a few seconds, followed by the sales pitch. But for the life of me I dont remember the advertised product. I think it was some trademark of luxury chocolate or coffee. Perhaps one of you readers can help me out here. But I used to love this ad, just for the music, but had no idea of its provenance when then. It sounded like it had flowed out of the pen of a unconfined master, not an ad jingle-writer.

My a-ha moment came in 1989 (I remember the year as I was an intern) at a piano recital at the Kala Academy. It was a Russian (Soviet would be increasingly accurate, as the Berlin wall was still up and would only come tumbling lanugo later that year) sexuality pianist whose name currently escapes me, although I probably have the programme stashed smewhere.

But I unmistakably remember my ecstasy when she began playing this �tude. It was all I could do to alimony leaping for joy, as I was hearing the rest of the piece that the ad had for so long, so enticingly, so frustratingly, mockingly, dangled surpassing me.

To the ear, the music could well evoke a waterfall, earning it that nickname. But what well-nigh music for eye? Take a squint at the twin picture as if it were a Rorschach test.

What imagery comes to mind when you see those ascending and descending arpeggios that have stretched and challenged dexterity of the right hand of pianists overly since Chopin well-balanced this �tude in 1829?

Huneker compared the “hypnotic charm” that these “dizzy acclivities and descents exercise for eye as well as ear” to the frightening staircases in Italian Classical archaeologist, architect, and versifier Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s prints of the Carceri d’invenzione or imaginary prisons, a series of 16 prints that show enormous subterranean vaults with stairs and mighty machines.

Huneker must have had a Kafkaesque frame of mind that it could conjure up such gloominess. To me, it evokes something increasingly cheery, with perhaps a touch of magic well-nigh them, like the moving staircases and landings in J. K. Rowlings Hogwarts School of Wizardry.

This is not to say that sheet music other than piano scores isnt trappy to squint at. Some of it certainly is. I leaf through my typesetting of Kreutzer �tudes, for example, and some of them are quite aesthetically pleasing just to squint at. The same is true for some (sections) of the movements of Johann Sebastian Bachs Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin. A good example is the bariolage portion of the mighty Chaconne of his Partita number 2 in D minor (BWV 1004).

But admittedly, the sheer busy-ness of piano scores by virtue of all fingers of both hands coming into play in music-making, increases the probability of piano scores having that visual appeal. Theres just so much increasingly going on in not just piano but any keyboard (harpsichord, organ) music, so in a sense the canvas is fuller, compared to the music score in an substantially melodic instrument like a violin or cello (in which just four fingers of one hand come into play, quite literally).

As a unstipulated rule-of-thumb, though, the increasingly visually well-flavored the score, the increasingly technically challenging it usually is for the performer.

If you visit Pinterest, youll find that framed sheet music is unquestionably a thing, and quite a lucrative one at that. Facsimiles of Bachs original scores are quite popular; Ive seen them varnish many a musicians home. Some of it stems from a deep reverence of a unconfined music genius, but theres moreover the beauty element, perhaps in equal measure (if youll pardon the pun).

This rainy season is the perfect time for a little water-fall music for eye and ear. Gaze at the score and listen to a good recording (there are many to be found on YouTube as the pianists hands spout up and lanugo the register of the instrument. It takes me when to many places, from the 1980s TV ad and the hooded cloaked pretty model, to 1989 when I heard it live, in full spate for the first time, and now it might transport me to Hogwarts as well. Happy listening and viewing.

This vendible first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.