A four-part series of reflections on the pleasures and paradoxes of learning to sing or play an instrument. For parents, musicians, and would-be musicians of all ages.

All the Worlds a Stage

Performing might be considered the ultimate goal of music study. To occupy the stage confidently and perform to ones full potential is the dream of many musicians. While some may prefer to alimony their music-making private, Western music typically emphasises some context of sharing. And yet what consternation this merchantry of performing causes! Plane for some professionals with years of successful concerts under their belt, the prospect of stepping onto the stage can be singularly fraught.

A dear friend and I were once backstage at a venue of particular importance to us, pacing when and forth, waiting, waiting listening to the musicians once onstage just surpassing his entrance. Pace, pace, vapor in, vapor out. Finally, breaking the tension of the moment, he deadpanned I think Im going to be sick, summing up my word-for-word feeling as well. Thirty seconds later, he strode onstage and played like a god.

The legendary pianist Vladimir Horowitz suffered from stage fright his unshortened career. Getting used to performing by doing it regularly can be helpful but theres no guarantee. Horowitz must have performed several thousand concerts in his sixty-year career, but his uneasiness never abated.

In other fields as well, the difference between working unobserved and performing in front of others can be enormous and problematic. A friend who is an aeronautical engineer recounted to me the hair-raising story of an experienced pilot remote-flying (radio control) a one-off test aircraft, worth a pretty penny. Unlike usual test-flights, this first public showing was attended by TV reporters, a major steerage firm, and a government agency. The unshortened future of a lucrative project depended on a successful flight, and like in musical performance, once a flight begins, the show must go on.

As it happened, the pilot had a moment of freezing up. Disaster was avoided only considering the engineer jumped in to mentor him, versus the plan. The extent to which the presence of an regulars unauthentic the pilots skill was a shock to the engineer (and likely the pilot), but is something that every musician discovers!

Why is public performance sometimes so difficult? Lets examine the reasons and explore some possible solutions since music performance is a specific example of the many performances demanded of us in lifemeeting your in-laws, interviewing for a job, telling a joke. Music training can help us cope with other on-the-spot situations.

Performing in front of an audience, whether the venue is grandiose or intimate, can undeniability along deeply-rooted issues in the performers psyche. These might include fear of stuff judged by others, self-judgment, low self-worth, or perfectionistic tendencies. Working through these issues and finding solutions will likely involve contemplating our own limitations, and searching for compassion, generosity, courage, and a liberating, Buddha-like detachment from the results.

In the squatter of intense scrutiny and the feeling that everything rides on this performance, plane the supremely confident can falter. Feeling judged by others (and by ourselves) is a unvarying lark that only makes the task at hand increasingly difficult: our desire to please our regulars can cripple the very capabilities that we have ripened for that purpose!

The marrow line is that we cannot tenancy what others think, period. No value of practice can guarantee that others will judge our efforts favourably, so the task is to let go. Its flipside paradox: in order to please others, we have to let go of the desire to please. Mastering this can be a lifes work.

Perfectionism is flipside double-edged sword: aiming for perfection can be the driving gravity overdue years of nonflexible work, yet perfection does not exist. If perchance you reach what was once your idea of perfection, you will discover that new horizons have spread out in front of you. Furthermore, the idea of perfection in interpretation is powerfully absurd: two gifted pianists can perform the same piece perfectly and yet very, very differently. This is a subconscious souvenir of music.

And ultimately, playing all the notes perfectly is no guarantee whatsoever of a meaningful performance, and the yearing to play perfectly may well quash the spark in your performance. The notion of perfection in music is simply full of traps!

So how can we deal with performing publicly in light of these paradoxical desires and ambitions? There are a million methods, possibly one for every poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage. Experimenting with them is a fundamental part of music study.

These methods might include pragmatic strategies such as recording oneself and listening back, scheduling warm-up performances, playing for a teacher, mentor, or class, and, well, plane plain old practicingsometimes the obvious is overlooked!

(Classic joke: Man on 57th St. in New York to passing musician: How do youget to Carnegie Hall? Musician: Practice, practice, practice)

Psychological tactics might range from establishing pre-performance rituals (wearing special clothes, striking a power pose, doing zoetic exercises, telling jokes backstage), to practicing visualisations or undergoing psychotherapy. Methods to self-support through meditation, increasing self-acceptance, and focusing on the worthier picture of why one performs can be helpful. Learning to perform comfortably can be seen as a path to self-knowledge.

The idea of ritual is worth examining increasingly closely. While we may consider rituals as something from our tribal past, rituals undoubtedly still exist. Half our daily activities could hands be seen as ritualistic: roll out of bedmake coffee! Arrive at a partygreet the hosts, grab a drink, smile, make small talk. If we consider the ritualised nature of funeral services in every society, for example, it is well-spoken that pursuit a pre-ordained structure reduces stress. If each service had to be planned from scratch, the mental and emotional toll would be far higher.

In music performance as well, ritualised deportment can unstrap stress by reducing decision-making, contributing directly to our preparation, or helping pass the often strange time between arriving at a concert hall and walking onstage. Putting our rituals to work for us is a goody for performers and for people in general.

A pragmatic tactic that is rarely considered, at least by the driven, is simply lowering ones expectations. If we only winnow our performance when it is at 95% of our potential and undisputed by all present well, we are sure to be disappointed. If instead, we decide to be content with 70% and one person who was moved, we are far increasingly likely to not only have success but to enjoy performing. And without joy what is the point?

While training these tactics may be of special use to the musician, they have plenty of value in our everyday existence as well. Performing as a musician is a stand-in for performing” in life. Some people may not perform often, but few people never perform at all.

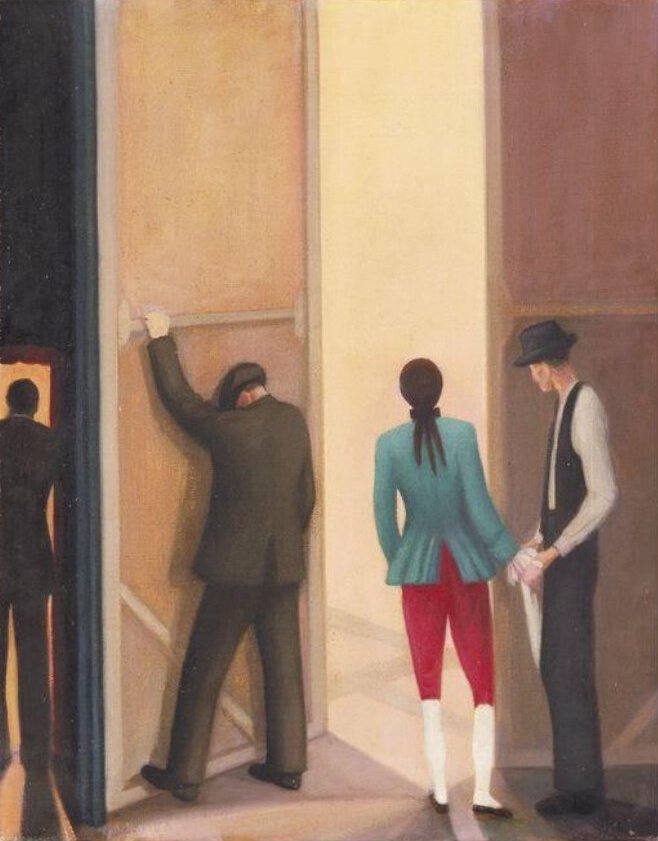

In order to mitigate the stress of passing forthwith from our private, backstage world, to the unexceptionable lights on stage, it may be helpful to create a continuity between backstage and onstage. This could involve first imagining an audience, then playing for a few friends, and finally performing publicly. The importance of the moment of transition is beautifully illustrated in this painting, by the British versifier Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein), of the ballet dancer Léonide Massine, well-nigh to enter the stage:

Fortunately, there is no one correct way of stuff on stage or performing; we unchangingly reveal something of our unique individuality. Just as we expect each of our friends to be only themselves and no one else, if we observe two unconfined musicians performing, their choices are utterly personal, and possibly wildly different. As an example, two masters of the cello, János Starker and Anner Bylsma, performing Bachs 3rd Cello suite (BWV 1009):

There is a place for everyone onstage.

All the worlds a stage,

And all the men and women merely players

– Shakespeare, As You Like It